Summary

Decision No. 2039 of January 26, 2018 by the Italian Supreme Court imposed joint and several liability on an art gallery and an artist for the sale of plagiarized works. The gallery’s role was characterized as a failure of due diligence and raises questions regarding the role of art dealers in perpetuating questionable art market practices. This decision and the recent Graham v. Prince case in New York have significant consequences for art market operators, setting a precedent of quasi-vicarious liability for artists’ unlawful acts. The importance of authenticity as a driving concept for these professionals is also explored, through a brief analysis of appropriation artists and applicable law.

Claudia S. Quiñones Vilá: What’s Mine is Yours (pdf)

What’s Mine is Yours: The Liability of Art Dealers for Artists’ Plagiarism According to Recent Developments in Italy and New York

By CLAUDIA S. Quiñones Vilá

The state of the art world is currently in flux and faces interesting challenges relating to the management and conception of what constitutes art. Globalization has resulted in greater access for artists and exhibition spaces to engage with audiences and obtain source material, as well as to challenge long-held assumptions of art as a singular process rather than a collaborative endeavor. Multiple players in the art market, such as art galleries and dealers, are gaining greater notoriety. But with fame comes responsibility – both ethical and legal.

Earlier this year, the Italian Supreme Court (Corte di Cassazione) issued a ruling concerning the legal responsibility of an art gallery for participating in the sale and display of plagiarized works (Decision no. 2039, January 26, 2018). Specifically, the Fondazione Emilio e Annabianca Vedova, representing celebrated Italian artist Emilio Vedova, claimed that paintings by another artist, Pierluigi de Lutti, constituted plagiarism, or unacknowledged copying, and that these paintings were used by the gallery as promotional material in addition to being offered for sale. The Foundation was originally created by the artist and his wife, with the primary goal of enhancing and studying Mr. Vedova’s artwork through various cultural initiatives, including study, research, and exhibitions. Mr. Vedova specified that the custody and preservation of his works could not be separated from his artistic philosophy, relating to the concepts of “painting-space-time-history.” Currently, the Foundation is chaired by an attorney, who must carry out this mission, including filing a lawsuit against De Lutti for plagiarism, since such actions violate Mr. Vedova’s insistence that his work be linked to his philosophy (Fondazione Emilio e Annabianca Vedova. Obiettivi e Finalità. http://www.fondazionevedova.org/la-fondazione/obiettivi-finalita).

In this case, the court characterized the gallery’s joint and several liability as a failure of due diligence according to Art. 1176 of the Italian Civil Code, which states that diligence in a professional context will be evaluated in consideration of the nature of the activity carried out (Italian Tort Law, http://italiantortlaw.altervista.org/civilcode.html).

Thus, this article was interpreted as imposing an affirmative duty of “qualified diligence” on experts in the art market to verify a work’s authenticity prior to engaging in commercial acts (Laura Turini. “The protection of intellectual works: the Court of Cassation summarizes the guiding principles in the judgment of plagiarism,” Brevetti News. 4/10/2018. http://brevettinews.it/en/copyright/protection-intellectual-works-courtcassation-summarizes-guiding-principles-judgment-plagiarism/). Good faith was not considered an adequate defense in these circumstances, as the mistake could have been avoided by using ordinary diligence for the sale of works of art. (CBM & Partners Studio Legale. Corte di Cassazione, 26 gennaio 2018, n. 2039, il plagio di opere d’arte e la responsabilità dell’operatore professionale. 5/11/2018. https://www.cbmlaw.it/corte-dicassazione-26-gennaio-2018-n-2039-il-plagio-di-opere-darte-e-la-responsabilitadelloperatore- professionale/).

In particular, a professional art market operator must provide official certificates of authenticity or provenance to a purchaser, or, alternatively, a statement containing all the available information regarding authenticity or probable attribution and provenance, as per Art. 64 of the Cultural Heritage Code (Codice dei Beni Culturale). The gallery did not provide the adequate documentation to satisfy this duty. Furthermore, the gallery had televised the works in question, which made the effects more widespread and was construed as evidence of their direct involvement and culpability.

However, an art dealer’s liability for plagiarism is not absolute, as there are varying degrees of knowledge that meet the threshold for due diligence. The concept of due diligence is defined separately in each jurisdiction, but often understood through the reasonableness standard; i.e., what a reasonable person would (or would not) do in a similar situation, taking into account their intelligence and experience. This means that, due to their high level of specialization and expertise, art market sellers are held to a stricter standard. While they are not vicariously liable per se, galleries have a complementary duty and their actions cannot be severed entirely from artists engaging in plagiarism. Another factor is that the art market has created an ongoing demand for masterpieces, with a limited supply of authentic works, which leads to “creative” solutions. In the words of Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr.: “The art market is tricky, unorganized, and unregulated… and in this market it pays very well for people to sell objects that aren’t what they purport to be.” (Christopher Reed, “Wrong! But a nice fake is valued object in a university museum,” Harvard Magazine, September-October 2004. http://harvardmagazine.com/2004/09/wrong.html)

Plagiarism, like forgery, calls into account the fair use, copyright, and moral rights doctrines. Contemporary appropriation artists have built their careers on skirting the line between what is acceptable and what is not, according to the law; Richard Prince is a notable example. Richard Prince was involved in a controversial fair use case in 2013, where he prevailed by demonstrating that his modifications to the original material were considerable and qualified as transformative fair use under U.S. law (Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013)). Prince is currently involved in litigation as a result of his 2014 New Portraits exhibit at the Gagosian Gallery in New York, illustrating how plagiarism is dealt with in U.S. courts (Gagosian Gallery New York. https://gagosian.com/exhibitions/2014/richard-prince-new-portraits/).

In this exhibit, Prince blew up photos from Instagram and added his own comments to them, selling pieces for up to $100,000 each. Buyers specifically purchased these works “because of Prince’s name attached, not because they want[ed] the original Instagram photo” (Krista L. Cox. Richard Prince: Thief, Appropriation Artist, Or Performance Artist? Above the Law, 10/18/2018. https://abovethelaw.com/2018/10/richard-prince-thief-appropriation-artist-or-performance-artist/?rf=1). One of the photographers, Donald Graham, sued Prince and the Gagosian Gallery for copyright infringement. Prince filed a motion to dismiss, once again on the grounds of fair use, but this time the judge ruled in favor of the plaintiff and the case has now proceeded to trial. At this stage, the court found that: “Because Prince has reproduced Graham’s portrait without significant aesthetic alterations, [it] is not transformative as a matter of law. Moreover, [it] is a work made with a distinctly commercial purpose; Graham’s original… is, without question, expressive and creative in nature; Prince’s use of the entirety of Graham’s photograph weighs against a finding of fair use.” (Graham v. Prince et al., 265 F.Supp.3d 366, 390 (SDNY 2017)). The gallery’s liability has not yet been determined, but its participation in Prince’s activities by including the photographs in the exhibition catalog and a prominent billboard display presents a parallel to the De Lutti case.

Interestingly, the Italian court did acknowledge that De Lutti’s works constituted a creative act, albeit in a minimal way, due to their small deviations from Vedova’s originals. The analysis focused on spatial and chromatic details and proportions, finding that they appeared simplified from Vedova’s but that the technique was essentially the same, “with repetition of stylistic modules without any different artistic meaning.” (Raffaella Pellegrino, “Plagio e opere d’arte. Il caso Vedova-De Lutti,” Artribune, 4/1/2018. https://www.artribune.com/professioni-e-professionisti/diritto/2018/04/plagio-emilio-vedova-pierluigi-de-lutti/ Translation mine). If De Lutti had stated instead that his works were “inspired by” Vedova, the result would likely have been quite different (Joss Saunders, Plagiarism and the law, Learned Publishing, Vol. 23, No. 4 (2010), p. 279-292). After all, it has been said that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. But foregoing the proper attribution is a dangerous game, as De Lutti and the gallery both learned. This situation reflects poorly on art dealers in a market where reputation is the ultimate form of currency. It remains to be seen whether lessons have indeed been learned, or the trend will continue. This decision should make art dealers wary of cutting corners where due diligence is concerned and wary of the artwork they include in their catalogs and promotional material over media networks, as this could be used as evidence of collaboration in a plagiarism case.

In sum, the De Lutti and Prince cases raise legal and ethical dilemmas as to the role – and possible collaboration – of art dealers in perpetuating the commercialization of questionable works, either as a publicity stunt or through plausible deniability. The art market is inherently subjective, and valuation is closely linked to authenticity (Joseph C. Gioconda, “Can Intellectual Property Laws Stem the Rising Tide of Art Forgeries?” 31 Hastings Comm. & Ent L.J. 47, (Fall 2008), p. 52-53). Experts and connoisseurs can make or break reputations with a single sentence. Artists and art dealers therefore operate under immense pressure to present works as authentic, even if this is not the case.

Professionals can exploit loopholes to drive up prices while using confidentiality as a shield, although increased scrutiny is shedding light on these practices (This is especially true for cultural artifacts; Christos Tsirogiannis, Something is Confidential in the State of Christie’s, Journal of Art Crime, Vol. 9 (2013), p. 4-5). At the moment, the Graham v. Prince case serves as a common law counterpoint to the De Lutti decision, exemplifying the willingness of U.S. courts to hold art dealers accountable for artists’ behavior. It will be interesting to see what arguments the Gagosian Gallery presents in its defense, as well as the jury’s response. Art dealers will suffer economic and reputational consequences if they turn a blind eye to plagiarism in the name of profit and marketing.

To be continued…

—

Claudia S. Quiñones Vilá is a licensed attorney who works in the field of art and cultural heritage law. She also holds degrees in art history, translation, and international dispute resolution. Currently, she is performing research at UNIDROIT in Rome.

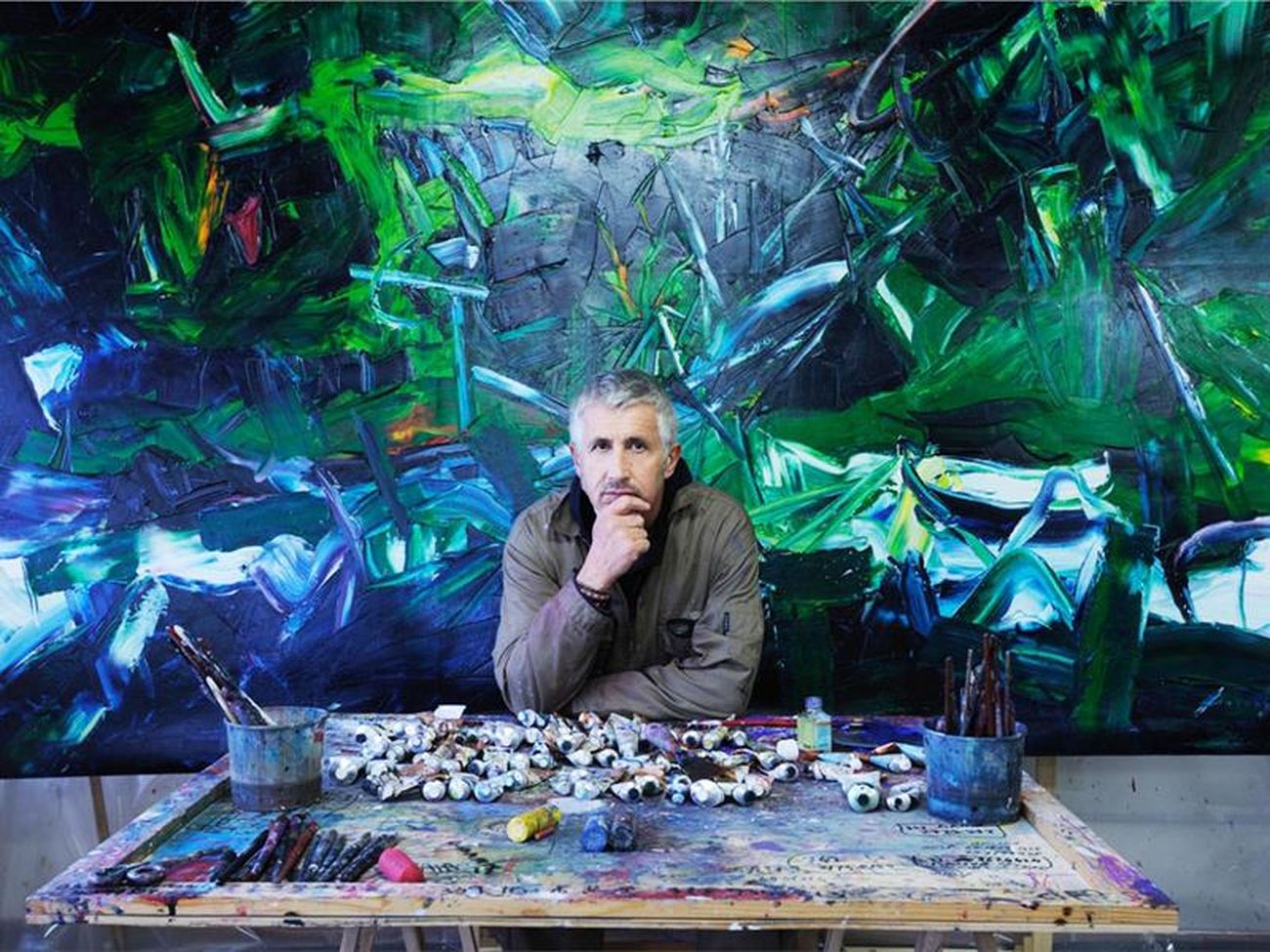

Images

- Artribune, Plagio e opere d’arte. Il caso Vedova-De Lutti. 4/1/2018.

https://www.artribune.com/professioni-e-professionisti/diritto/2018/04/plagio-emilio-vedova-pierluigi-de-lutti/ - Emilio Vedova, Mose fa scaturire l’acqua dalla roccia (1942). Museo Novecento, Firenze.

http://www.museonovecento.it/collezioni/mose-fa-scaturire-lacqua-dalla-roccia/ - Rob McKeever, Installation photograph. https://gagosian.com/exhibitions/2014/richard-prince-new-portraits/

You must be logged in to post a comment.